Writing female characters seems to be a difficult thing to do for most screenwriters and tv writers. Bad female characters seem to be the rule rather than the exception. But there are writers working hard to change this paradigm, by introducing and developing their female characters with a bit more care and realism. And by doing so, they’re not just “catering to female gatekeepers” or being “politically correct” – they’re writing stronger scripts and better stories.

No matter your gender, or your ethnicity, or your political viewpoint, you’ve probably absorbed much more of the film industry’s innate sexism than you realize and, as a screenwriter, your default writing choices when it comes to gender may reflect as much.

The good news is there are ways to consciously counteract any gender bias you may not be aware of in your writing. For many, that bias is sometimes referred to as the “Default Male Syndrome” or “Default White Male Syndrome.” Here’s a few things writers can do to combat those innate biases:

To write strong female characters, don’t write sex objects

You’d be surprised how often otherwise-professional writers dish up female character descriptions like this:

JANE (20) — is incredibly hot but doesn’t know it.

What does this mean? Usually that the screenwriter wants to find someone like this for themselves. It’s common for writers to create characters they fantasize about. But this character description basically translates to

JANE (20) — hot, but might still sleep with me.

Another variant of the same scenario might be something like this:

JANE (20) — pretty but with intelligent eyes.

Which boils down to the writer telling us that the most important thing to know about this character is that this character is pretty. But more telling is that the writer is also warning us not think that just because this character may be pretty doesn’t mean she’s stupid. Yet when you think about that for a moment, the question becomes: why would there be any reason in the world for a reader to assume that just because a character is pretty that they also must be stupid?

Further, when was the last time you read a character description like this:

JOHN (20) — incredibly hot but doesn’t know it.

or

JOHN (20) — handsome, but with intelligent eyes.

Even if you have seen descriptions like this for male roles, it’s still bad screenwriting.

Write female characters, not has-beens

This is his wife JANE, 35, a fading beauty who’s still attractive for her age.

Cringe.

The movie industry caters to a mass audience. As such, it can often reflect and reinforce some of society’s most repugnant views on women. One of these views is that women over the age of 30 and definitely women over the age of 45 are, by default, considered unattractive. Unsurprisingly, most women of any age neither appreciate nor agree with that viewpoint.

So instead writing about her beauty, how about we find out something else about Jane, such as how she feels, or who she is? What could Jane be? Many things.

JANE (35) — practically-dressed but with her mind always off dreaming of elsewhere.

Or

JANE (49) — perfectly turned out, watchful as she enters the room.

Hair, make-up, and wardrobe can also tell us a lot about character, but the best way to convey a character is often by how they behave or move the first time we see them.

The point is, descriptions can be physical but should rarely be a value judgment. You may notice how the women male stars date (both on and off-screen) remain the same age even as the male stars hit their 50s, 60s, and even 70s. This may be the world we live in, but perhaps it’s time to change the world.

Write female characters, not just appendages of the male ego

A female character needs their own journey. If everything in their story is related to the male hero’s story, seek ways that the male story changes them in a meaningful way. At all costs, avoid “awarding” the girl or woman to the guy as some kind of prize when they start behaving better, win their sports match, solve the crime, take over the cartel, or all of the above.

It’s been done to death.

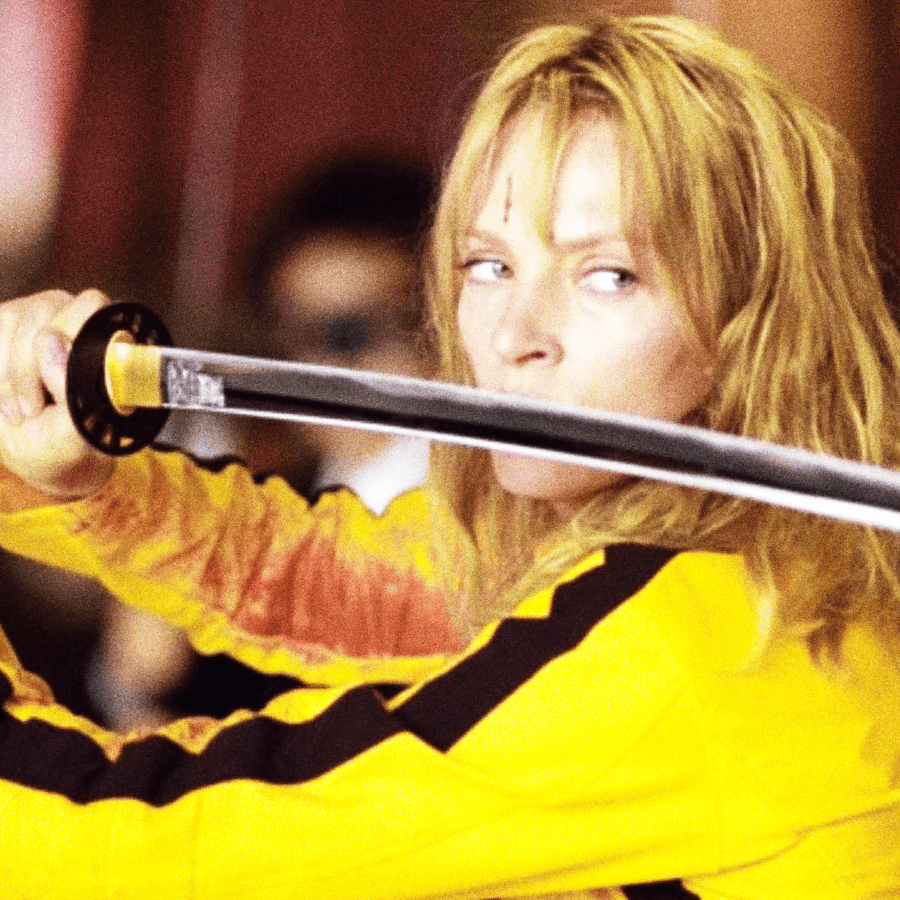

Write female protagonists, not just female supporting roles

If you’ve come up with a story about a cynical, damaged police detective who finds a way to care about their work again when they have to solve a crime that resonates with them in a painful and personal way, consider making that classic noir archetype a woman, rather than a man.

The same applies to every character in your story. Choose. Don’t default. The result could well be a more interesting project.

Write women and girls who have something to say

Does your script include

1. at least two women

2. who talk to each other

3. about something other than a man?

If so, it passes the “Bechdel Test,” but there’s more to the story than that.

It also matters very much how much women get to speak, and whether what they say is meaningful. In 2016, women spoke only 27% of the dialogue in the top-grossing films of the year. Does this mean films in which women speak will fail? Probably not. It’s more likely that they were all written from a male point-of-view. About 7% were directed by women and only 11% written by women.

Coincidence? Unlikely.

One of the sure sign of bad writing: female characters don’t get to be real people. While writing is largely about instincts and imagination, challenge yourself at every turn. Original and attention-grabbing storytelling isn’t an accident. It’s partly about making a different and sometimes less obvious choice in terms of how your characters convey universal and eternal life truths. Your female characters can be part of that process.